-

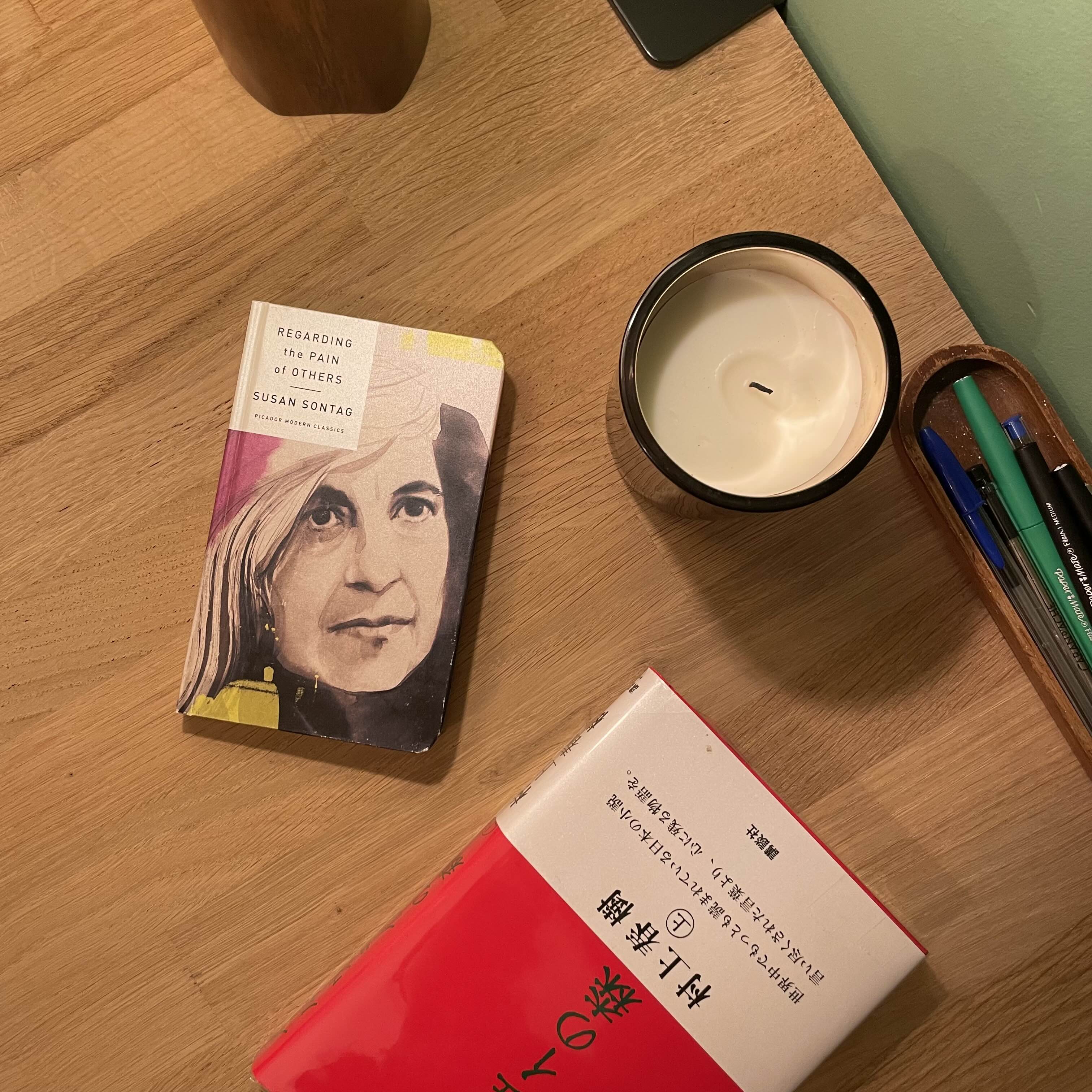

Regarding the Pain of Others일상/book 2022. 3. 9. 06:17

Regarding the Pain of Others/Susan Sontag/Picardo Modern Classics "우리는 사진을 통해 기억하는 것이 아니라, 사진만을 기억한다.The problem is not that people remember through photographs, but that they remember only the photographs." 우리는 너무나도 많은 이미지 속에 살아가는 나머지, 이미지에 너무 둔감해져서 우리가 어떤 이미지의 영향을 받으며 살아가는지, 어떤 이미지를 취사선택하는지조차 모른 채 살아간다. 그런 의미에서 알아야 할 것을 아는 것이 아니라, 보이는 것만을 안다는 수전 손택의 말은 틀리지 않다. 우리는 이미지 속 누군가의 고통스런 모습을 보아도 상투적으로 가볍게 반응할 뿐, 그 고통을 헤아리지는 못한다.

사진은 19세기 말엽부터 회화(繪畵)를 대체해 '타인의 고통'을 전달하는 매체로써 본격적인 기능을 수행해 왔다. 19세기와 20세기를 수놓았던 무수히 많은 전쟁들—크림전쟁, 스페인내전, 양차 세계대전—은 종군 사진작가들이 전장(戰場)의 참상을 기록으로 남기는 무대가 되었고, 기록된 사진은 신문이라는 새로운 대중매체를 통해 관객들에게 소비되었다. 다른 한편으로 전쟁장면은 군의 사기(morale)를 고려한 각국 정부의 규제하에 수위가 통제되거나 심지어는 연출되기도 했는데, 사진 속 희생자의 고통이 사회적 반향을 일으켜 거대한 사회 운동으로 이어진 것은 베트남 전쟁의 사례가 거의 유일하다.

우리는 흔히 사진이 회화보다 현실을 더 충실히 담는다고 하지만, 그러한 사진 속 현실조차 렌즈를 다루는 이의 관점을 반영하고 있다. 서구 사회가 주도해 온 매체물로써의 사진과 카메라는 역사적 맥락을 들여다보면 비뚤어진 관점을 관객에게 전달한다는 것을 알 수 있다. 서구 사회와 밀접하게 관련이 있는 전쟁들은 비중 있게 조명되지만, 그렇지 않은 사건들은 대개 외면받는다. (심지어 수전 손택의 이 글에서조차 본문에 거론되는 무수히 많은 전쟁들 가운데 한국전쟁에 대한 언급은 단 한 줄도 없다.) 2015년 레바논 테러는 파리 테러와 하루 차이를 두고 발생했지만, 이제 와 레바논 테러를 기억하는 사람은 거의 없다. 수전 손택이 꼬집듯이, 양차대전에서 희생된 유대인들을 기리는 기념관을 세워야 한다는 미국인들이 정작 건국과정에서 희생된 노예를 기리는 기념관을 세워야 한다는 이야기는 거론조차 하지 않는다. 그것이 서구에 의한 것이든 제국에 의한 것이든 타인의 고통을 담는 시선은 이처럼 편향될 수밖에 없다. 매체를 이용하는 이들은 자신들이 절대선이고 싶어한다.

나아가 사진술이 발달하면 발달할 수록 사진이 최초에 분리되어 나왔던 회화와 비슷한 성격을 띠게 된다는 아이러니가 발생한다. 이 역시 수전 손택이 지적하는 내용으로, 2001년 9.11 테러 영상을 접한 미국사람들은 '초현실적(surrealistic)', '영화 같다'와 같이 미학적인 표현을 쓰는데, 이는 사실 고통을 절실히 공감했다면 쉽게 쓸 수 있는 어휘가 아니다. 사진을 보정하고, 불필요한 부분은 제거하면서 사진은 회화와 비슷한 성격의 아트가 되어가고 있고 관객들을 특정한 방식으로 호도하기 시작한다. 뿐만 아니라 미디어의 발달로 인해 사람들은 본인이 원하는 영상을 취사선택하여 시청할 수 있다. 눈은 눈꺼풀로 덮을 수 있지만 귀는 닫을 덮개가 없다는 수전 손택의 비유대로, 시각이라는 감각은 우리의 편의에 알맞게 발달해서 관객 본인이 눈을 감고 싶은 영상에 눈을 감아버리면 그만이다. 실상 끔찍하고 마음 아픈 영상을 세 시간이고 네 시간이고 틀어놓고 보고 싶어하는 사람도 물론 없거니와.

때문에 수전 손택은 '보는' 행위만으로 타인의 고통을 헤아리려 할 것이 아니라, '행동'을 통해 타인의 고통에 공감을 표해야 한다고 말한다. 보는 행위는 있는 그 자리에서 타인이 고통을 경험하는 장면을 망막으로 흡수할 뿐이다. 어쩌면 오늘날 사람들이 가짜뉴스에 쉽게 현혹되고 점점 더 영상물에 무비판적으로 빠져드는 것은, 수전 손택의 말대로 우리가 이미지와의 관계에서 어떤 위치에 있는지에 대한 아무런 비판적 사고 없이 아득히 둔감해져버린 나머지 생기는 문제인지도 모른다. 비유하자면 비만 상태에 있는 사람처럼, 이미지를 과잉으로 접하고 있지만 이미지를 수용하고 있는 우리는 과연 정말로 건강한 상태에 있는 것일까. 타인의 고통에 진정 손내밀 줄 아는 예양을 갖추고 있을까. 수전 손택의 글을 읽으며 여러 생각을 떠올려보게 된다. [Fin]

Technically, the possibilities for doctoring or electronically manipulating pictures are greater than ever—almost unlimited. But the practice of inventing dramatic news pictures, staging them for the camera, seems on its way to becoming a lost art.

—p. 72

……it makes sense if understood as obscuring a host of concerns and anxieties about public order and public morale that cannot be named, as well as pointing to the inability otherwise to formulate or defend traditional conventions of how to mourn. What can be shown, what should not be shown—few issues arouse more public clamor.

—p. 86

The exhibition in photographs of cruelties inflicted on those with darker complexions in exotic countries continues this offering, oblivious to the considerations that deter such displays of our own victims of violence; for the other, even when not an enemy, is regarded only as someone to be seen, not someone (like us) who also sees.

—p. 91

The idea does not sit well when applied to images taken by cameras: to find beauty in war photographs seems heartless. But the landscape of devastations is still a landscape. There is beauty of photographs of the World Trade Center ruins in the months following the attack seemed frivolous, sacrilegious. The most people dared say was that the photographs were “surreal,” a hectic euphemism behind which the disgraced notion of beauty cowered.

—p. 95

It also invites them to feel that the sufferings and misfortunes are too vast, too irrevocable, too epic to be much changed by any local political intervention. With a subject conceived on this scale, compassion can only flounder—and make abstract, But all politics, like all of history, is concrete.

—p. 100

Shock can wear off. Even if it doesn’t, one can not look. People have means to defend themselves against what is upsetting. ……do people want to be horrified? Probably not.

—p. 103, 105

All memory is individual, unreproducible—it dies with each person. What is called collective memory is not a remembering but a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about how it happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds.

—p. 108

The problem is not that people remember through photographs, but that they remember only the photographs.

—p. 112

It is a view of suffering, of the pain of others, that is rooted in religious thinking, which links pain to sacrifice, sacrifice to exaltation—a view that could not be more alien to a modern sensibility, which regards suffering as something that is a mistake or an accident or a crime. Something to be fixed. Something to be refused. Something that makes one feel powerless.

—p. 126

People don’t become inured to what they are shown because of the quantity of images dumped on them. It is passivity that dulls feeling.

—p. 130

'일상 > book' 카테고리의 다른 글

토지 6 (0) 2022.03.28 노르웨이의 숲 (ノルウェイの森/上) (0) 2022.03.21 토지 5 (0) 2022.02.28 토지 1부—하동(河東) 이야기를 읽고 (0) 2022.02.26 토지 4 (0) 2022.02.24